“Start thinking and feeling”: Haseeb Iqbal on London jazz and grassroots community

Haseeb Iqbal is something of a shapeshifter.

In one mode, the 24-year-old London native is an active participant in his city’s much-talked-about contemporary jazz culture as a mastermind behind the popular record-spinning nights Studio Crumb and Chessidency. In another, he’s a self-reflective theorist and historian–the author of both a 2021 Rough Trade book on the forces that shaped his scene (Noting Voices: Contemplating London’s Culture) and pieces on global jazz history for outlets like The Guardian. And, somewhere in the middle of these, he was–up until the station’s recent closure–the host of a documentary- and interview-laden Worldwide FM radio show designed to offer “context to the culture.” Now, without having missed a week following its termination, he is several broadcasts deep into a new independent show over at haseebiqbal.world.

What strikes me most about Haseeb’s varied work, however, is not its prolificness or insightfulness–though it certainly typifies those things–but its multimodal, boundary-breaking approach. Whether working through the pen or the airwave, Haseeb always seems intensely aware of how the thing he’s doing right now is in touch with a wider, deeper context–whether it be another art form, history, place, community, social mode of being–and holds an accordant conviction about its significance.

This kind of awakened conviction is rare in the world we live in, and something I have often strived–and struggled–to cultivate myself. As such, when I got the opportunity to meet Haseeb in person one lovely October afternoon at a cafe near his studio in Stoke Newington, London, I went into it full of ideas about dissecting the way his perspective has been formed. I had several pagefuls of questions prepared. Among them: What was its origin? In what ways has it been influenced by the ethos of contemporary London jazz? How conscious are its principles?

Haseeb, for his part, arrived slightly under the weather, having just come off of a busy four-day music festival. This didn’t stop him, however, from proceeding–over the next hour’s worth of tea and coffee–to smash and reassemble each one of the assumed frames I’d brought to the conversation with alertness, generosity and enthusiasm.

His initial response to my questions about his musical foundations did not immediately foretell this. He talked about the influence of his older sisters Nabihah and Tanya in introducing him to eclectic music early on, including sounds ranging from “So Solid Crew garage collective to quite rock-y stuff like The Smiths and The Cure”; his crucial acquisition of Kanye’s The College Dropout on CD at 6 years old, which led to a lifelong (but recently especially-fraught) appreciation of West’s music; the fact that whether it was Bob Marley or the Jonas Brothers, he “always loved” music, and “was never like semi-into” it.

But, soon enough, he turned and took us in a broader direction than my questions had anticipated, touching on some of the musical and cultural barriers that he did face as a youngster: “I [grew up] in northwest London. And… not being a white person, I was quite a minority. I grew up in a very white, white area and a white community. So for a while you don't really press against that… But then I got quite curious and open and was searching from quite a young age. When I was like 13, 14, me and a couple of my mates would just go out on summer holidays… all night long. We’d chat to strangers, we’d go to strangers' houses; we’d have all night to speak to random people, hang out with homeless people.”

As I listened, fascinated, to his account of these “important couple years,” Haseeb was already challenging the script I had unconsciously laid out in my head about how 21st-century musical discovery–or even general preference- and perspective-building–works. While I had instinctively imagined (from my own experience, I suppose) a rather solitary, atomistic exploration of cultural consumption, it was a physical encounter with people and places that allowed Haseeb to start contacting and learning from the many different perspectives that “paint [his] city… like a tapestry of magic.” For it was on this literal path of exploration that a 16-year-old Haseeb began to attend South London gigs by then-underground British hip-hop/neo-soul artists like Tom Misch and Loyle Carner, and so contacted the musical dimension of his “London awakening.”

It accelerated even more when he saw the opener for a November 2015 Loyle Carner gig—a genre-bending London group called Hester—and their performance became, with its broadening marriage of soul, indie, and jazz, “the greatest show [he’d] ever seen at that point.” This honor was only to be overturned a few years later by Ezra Collective at Brainchild Festival, where Haseeb really first saw “live music kind of becoming club music” in the way that new wave London jazz has become known for. He was hooked—and not just by the sounds of this budding culture, but by the openness, inclusiveness and “sincerity” he found in the attitudes of its creators. He clearly remembers the pivotal moment when, as a 17-year-old attending South London’s STEEZ jam night for the first time—per the recommendation of a member of Hester he’d gotten to know—he summoned the courage to perform a poem at the open mic, and suddenly found himself receiving the unequivocal support and “warmth of the room.”

It hit home for Haseeb–as it suddenly did a bit for me, hearing him explain it–that one could be a full participant in culture, not just a passive observer. “I [didn’t] feel any different than the people that I'm seeing headlining these gigs,” he told me. “I actually [felt] like I could mobilize and activate these ideas within me and there’s a place where people will receive them, there’s a place where people will appreciate them.” One of Haseeb’s subsequent ideas was to, at 20 years old, interview the founders of some of the most important venues in the scene (Brainchild’s Marina Blake and Total Refreshment Center’s Alexis Blondel among them) in an effort to trace the history of the spaces that had so inspired him. The end result was his Mare Street Records podcast, which later formed the basis for his book Noting Voices. In both, Haseeb captures the importance of these venues—with their inclusive, risk-taking lineups and nonhierarchical treatment of both artists and attendees—for allowing now-massive London jazz groups like Kokoroko, Sons of Kemet and Maisha the room to experiment and first find an audience.

“In order to create a space which has that… philosophy,” he noted to me, “respect comes first, helpfulness comes first, and ego kind of goes down a little bit… everyone tunes into something greater than themselves. That’s one of the magical things that underpinned all of those spaces.” It’s an approach that now also infuses Haseeb’s own idiosyncratic Studio Crumb parties, where he and fellow DJ Bror Havnes play 5 hour sets of all-vinyl records, zipping between “jazz tunes at 2 am followed by drum and bass.”

Though I’d read his book and some of what he was telling me about his initiation into the culture was familiar, having Haseeb trace the chain of inspiration to me in the flesh was beginning to be unexpectedly (though fittingly) demystifying. It started to occur to me that I had, from a distance, been treating his viewpoint and influence as somewhat untouchable and mysterious–the possession of a savant. Now it was striking me as more the product of an organic process of experience, curiosity and experimentation.

Still, clinging a bit to the narratives I’d come up with myself, I asked Haseeb whether the term “community” might better describe the like-minded sphere he’s found himself a prominent participant in than “scene”--a word which he notes in his book can come across as exclusive. But he was cautious even with that characterization, saying, “Maybe some people feel like [“community”] means, ‘By the end of the night I need to know everyone in there, I need to meet everyone.’ It’s kind of not… totally like that.” He has gotten to know so many people at Brainchild Festival that, by 2021, he would see “at least two people every 20 seconds... nonstop”—but that was a gradual development over five years of attendance.

“I never was like, ‘Oh yeah, my aim is to be a central part of this community and bring loads of people together,’” he told me. “My aim was just to feel a part of it and to keep being a part of it.” Likewise, Haseeb deems it most important that any event or space simply focus on allowing “people to feel comfortable within them. It doesn't need to be too much deeper than that at first… not like, ‘We are a community, you are now a member of our community.’” He pointed back to the undogmatic ethos of his own Studio Crumb party—“I'm just there to express myself with music.” He’s not even necessarily there to please the crowd: “If people are feeling it, then let's all feel it together. That's what it is.”

This goes against most conventional wisdom about the function of a DJ, but Haseeb trusts the relational, organic elements of music first. “People go to a club to escape the algorithm,” he posited. “Like for me… if I'm in it, if I'm in a club with like my favorite DJs ever—the deepest tunes I've ever heard—I don't [record or Shazam songs]. Because it quite simply just snaps me out of the trance... It's not the same. You know, the club night… it's like a painting. It's like a piece of theater, you know? You go through phases, you go through emotions. There is tempo, speed, intensity, softness, all of this stuff. But in order to really feel it, you've got to offer your entire self to it.” At Haseeb’s parties, he encourages attendees to come up to him at the end of the night and describe a song to him rather than Shazam-ing, “because it forces you to use a part of your brain that humans are losing now. Everything's on our screens. So, you know, stop typing, stop touching and start thinking and feeling.”

Indeed, if one thing was becoming clear by this point in the conversation, it was that Haseeb’s integrated perspective and approach was not a purely intellectual one. If, rather than being the product of an isolated struggle to contrive rigid plans or principles, it was more the result of listening, learning and building from the ground up–then perhaps the ground is the same sincere thread of wonder and spirit that inspired musical heroes of his like Pharaoh Sanders and Hugh Mundell.

If what you’re doing is “fulfilling your heart,” he continued, that can’t be taken away by external variables like popularity or cash-flow. Besides, a community can start with “two people,” and Haseeb assured me–seemingly from experience–that club nights where “there’s just nobody that has come… are as integral to the process as the ones that go off.” They’re not as much talked about, but he thinks they should be, and notes that “you just don't feel as proud of yourself [if the night goes off] if you haven't gone through the struggle where nobody's come.”

Such an unflappable willingness to field rejection and embrace necessary change can be difficult to maintain, Haseeb acknowledged—but, like Miles Davis or Alice and John Coltrane shattering the jazz rule book to make way for genres like fusion and spiritual jazz, it’s ultimately necessary if new beauty is to be created. This is the case, he maintained, even in the face of seemingly unpleasant events, like Worldwide FM ending. “We've got to create a world where people don't feel defeated by the radio going, and people feel like, ‘Right, now it's time to start something else,’” he insisted. “It's like the second law of thermodynamics—energy cannot be created nor destroyed. It can only be transferred.” It might be a bit annoying that the energy contained in Worldwide FM is scattered now—it maybe becomes a bit “less potent”—but Haseeb was confident that it will eventually build into a new concentration.

“We just gotta take care of the spaces,” he told me. “The physical space is so important, especially when there's so much occupation of the digital space right now. We can't we can't let that become the kind of frontier by which young people are introduced to culture solely. That's why a city like London is very important—because of the spaces that it has. So I think we need to make sure that we protect the spaces and… keep up the momentum and keep up the energy”—whether that means something as simple as holding an open mic at a pub that’s never had one before, or even just showing up to an event to soak in someone’s work and perspective.

This is even more important at a time when, as Haseeb described, youth clubs in England have seen 30-40% reductions in London, and 70-80% in parts of the north over the past decade–meaning that “disenfranchised kids from poorer families haven't got spaces to go and express themselves” in the way that some of the artists who now lead UK jazz did. Similarly, a few of the most integral spaces for the London jazz scene have been forced to dissolve or reduce operations in the past few years due to rising rents and maintenance costs—including not just Worldwide FM, but, quite recently, Brainchild Festival 2022. I asked Haseeb if he thinks some contact will eventually need to be made with the entities who do have the power of (often government-granted) money—i.e., the Barbican and BBC Proms, who Haseeb observed actually depend on small venues to feed them new talent—if some independent spaces are to have a longer lifespan.

“Yes,” he replied, but, “I think it needs to be on the shoulders of those bigger structures not only to help, but to kind of dialogue with [the smaller spaces].” He mentioned a recent exclusivity clause invoked by Love Supreme Festival that shut some artists out from playing more local festivals. “There needs to be a dialogue that exists between different-sized structures in order to make sure that the thread of culture is healthy. I don't know how we implement that, but there need to be a few regulations I think.”

Ultimately, though, Haseeb seemed more focused on being a dynamic force of creation than relying on any one structure. When considering the massive growth of his own fortnightly Chessidency night, where he and DJ Donna Leake spin contemplative and experimental records while a crowd of attendees play chess, Haseeb emphasized that its longevity has really just been a result of “maintaining sincerity and dedication to the ethos with which it began,” which is to offer “a counter experience to culture” by providing people a way to relax mid-week. Indeed, the notion of perseverance seemed to be at the center of much for Haseeb. “It's about maintaining enthusiasm,” he told me. “That's the most important thing in life.”

And so, while he would love to take Chessidency or Studio Crumb to more cities and even other countries, the root motivation for doing so will continue to be the effusion of a shared human experience that offers “escape from the algorithm, escape from the screens,” out into the enchantment of reality. And to do that requires attention, patience and consistency—without ever letting go of one’s thread of enthusiasm.

“There's so much that I feel like we've got to be inspired by. You know, even talking to you, it's so important… for me, my own spirit, to have this chat with you and to see your curiosity and enthusiasm,” he shared near the end of our conversation. “It’s very warming and inspiring.” To hear this was surprising and gratifying for me, because I felt like I was receiving the same, if not more–a nourishing peek through a lens capable of revealing the potential beauty in every community center, hand-me-down saxophone and apparent digression we encounter.

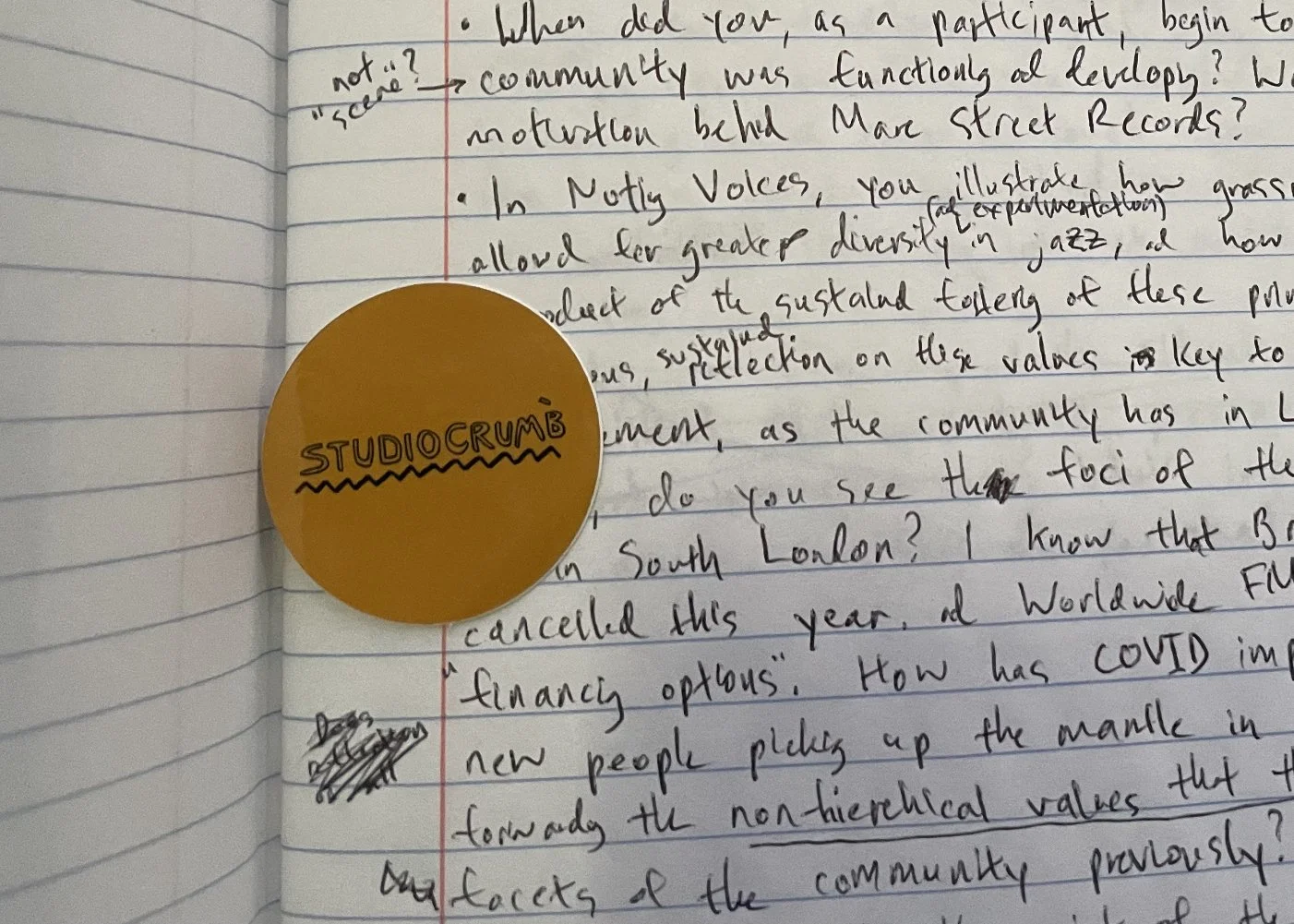

I am reminded of when, earlier on in our discussion, Haseeb all of a sudden announced that he’d brought a gift for me. He quickly produced something small and flat out of what appeared to be thin air. As he handed it over, I recognized it to be a yellow and white Studio Crumb sticker. I was delighted.

“It’s just a little sticker,” he noted. But it was also the first official piece of merch that he and his partner had created for the night, he informed me—and I was now, after them, precisely the third person in the world to receive one. I thanked him, telling him truthfully that it meant a lot, and that I was going to keep tight hold of it.